http://www.architectmagazine.com/exhibitions/small-scale-minor-letdown.aspx

Exhibition Page

_reflections and musings on texts and artworks explored this fall semester with smattering of relevant images and articles

21.11.10

19.11.10

Reevaluating Urban Form

I have just begun reading Design for Ecological Democracy by Randy Hester, Professor Emeritus of Landscape Architecture & Environmental Planning and Urban Design at UC Berkely and author of several community planning texts. In a nutshell, the book is about redefining and recreating the American city. This remade city would be ecologically and socially integrated and concerned with local knowledge and community participation.

In the Introduction,Hester critiques current American urban development and design; and points to it as the underlying critical issue that has destroyed the ‘sense of community’ and ecological richness in our cities and has lead to environmental crisis. “City makers continues to design urban areas more and more the same and less and less particular to to the vegetative mosaics,microclimates,air-movement patterns, and hydrologic cycles. We still call resulting urban wildfires,energy shortages and flood damage “natural disasters"(Hester 2).

With the same basic argument of many(many,many) Hester discusses the disconnect from surrounding nature caused by technology,the automobile,poor planning,ect. However while this remains an obvious problem in the developed world, I feel his argument could be a bit more thorough and..recent. He calls for a response of applied ecology and democracy(hence the books title) which leads to “actions guided by understanding natural processes and social relationships within our locality and larger environmental context”, and there fore a new urban ecology (Hester 4).

He introduces "3 fundamental roots to reformulate better cities":

1. our cities and landscapes must enable us to act where we are now debilitated(which according to Hester is almost everywhere down to our un-anchored soul)

2.) our cities and landscapes must be made to withstand short term shocks to which both are vulnerable.

3.) our cities and landscapes must be alluring rather than simply consumptive or conversely,limiting.

This new thought foundation is encompassed by a "global design process" which is participatory,scientific and adventuresome (Hester 8).

Successful and productive design is::

-inspired by local environmental processes

-ecologically and culturally diverse

-contextually response

to be cont....

In the Introduction,Hester critiques current American urban development and design; and points to it as the underlying critical issue that has destroyed the ‘sense of community’ and ecological richness in our cities and has lead to environmental crisis. “City makers continues to design urban areas more and more the same and less and less particular to to the vegetative mosaics,microclimates,air-movement patterns, and hydrologic cycles. We still call resulting urban wildfires,energy shortages and flood damage “natural disasters"(Hester 2).

With the same basic argument of many(many,many) Hester discusses the disconnect from surrounding nature caused by technology,the automobile,poor planning,ect. However while this remains an obvious problem in the developed world, I feel his argument could be a bit more thorough and..recent. He calls for a response of applied ecology and democracy(hence the books title) which leads to “actions guided by understanding natural processes and social relationships within our locality and larger environmental context”, and there fore a new urban ecology (Hester 4).

He introduces "3 fundamental roots to reformulate better cities":

1. our cities and landscapes must enable us to act where we are now debilitated(which according to Hester is almost everywhere down to our un-anchored soul)

2.) our cities and landscapes must be made to withstand short term shocks to which both are vulnerable.

3.) our cities and landscapes must be alluring rather than simply consumptive or conversely,limiting.

This new thought foundation is encompassed by a "global design process" which is participatory,scientific and adventuresome (Hester 8).

Successful and productive design is::

-inspired by local environmental processes

-ecologically and culturally diverse

-contextually response

to be cont....

16.11.10

Defining Environmental Architecture

This week I sped forward through the literature from early 70's to arrive at the present debate of sustainable design:What is sustainable? How do you design sustainably? ect. ect. Living in the age of "green washing", where for every product there seems to exist an alternative that is natural, organic, green, eco-friendly, many don't question the actual defining parameters of these terms

In,Taking Shape:A New Contract between Architecture and Nature, author Susannah Hagan calls for a redefinition of sustainable architecture. Hagan argues that creating a new sustainable design process based upon environmental ethic and not aesthetics will ultimately fail. She introduces three criteria which engage with environmental design and can act as tools to examine the idea of "sustainable".

1-Symbiosis: considers the building's life cycle and recognises the dynamic interrelated system of the environment

2-Differentiation: "considers whether biological diversity implies cultural diversity".

Looks to architectural diversity and what environmental advantage may be gained by pursuing it.

Looks to architectural diversity and what environmental advantage may be gained by pursuing it.

3-Visibility: "considers if all existing forms and theories are the only options”.

“The criterion of ‘visibility’ therefore asks whether this push towards conscious signification should not be included in environmental architecture. The issues of visibility pushes beyond architecture made sustainable:it marks out the ground on which some environmental architecture doubles back to architecture as art, that is to directed expression.”

Also, included in the reading in the chapter, “Rules of Engagement”, Hagan argues for a a restructuring of the BREEAM rating system, which is Britain’s equivalent to the U.S. LEED evaluating system. While the argument is a bit outdated at present, since this publication the BREEAM system has revamped their criterion for buildings achieving rated status, Hagan holds the same stance on the issue as many LEED skeptics to in the United States. Hagan contends that the rating system is superficial and undemanding and, “the most problematic aspect of the award, however, is the fact that is based on work done at design stage and not when the building is up and running”. She calls for a more holistic design and building approach:

“A symbiotic relationship is only possible if the building flights entropy like a natural system ,blurring the line between the man made and the given”.

Earlier this year, Frank Ghery defended his criticism of the LEED rating system in the U.S:

Ghery believes sustainable building concerns to be too “political” and LEED awards superficial and “bogus” in nature. While a skeptic of the LEED rating system myself, I am a proponent of sustainable design and believe there must be accountability in the design/build/operation. To call these issues political is unreasonable and "short sighted".

Good write up on Ghery:

ECT.

"Green wash" critique

Thankfully, there are still those who disagree with Ghery...

http://inhabitat.com/2010/11/16/spanish-highrise-keeps-its-cool-under-a-double-skin/#more-186992

7.11.10

On Robert Smithson:Heterotopia,Entropy,Language

In Chapter 3 of Earthworks, Susan Boetteger introduces Foucault's idea of "heterotopia" and its connection to earth work sites.

Foucault defines “heterotopia” in his 1986 article "Of Other Spaces":

“Places of these kind are outside of all places,even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality. Because these places are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about, I shall call them by the way of contrast to utopias, heterotopias”

Boetteger also employs Foucault's description, while initially used to describe social institutions, as applicable to art works which “simultaneously represent, contest and invert” not only only literal vertical,circumscribed masses but also the social ideal of sculptured monuments”.

Robert Smithson provides a prime example of an artist who embraced Foucaultian ideas of place and projected them into his in his sculptured environments. His fascination with entropy in the physical landscape through unnatural processes is investigated by Boetteger and became of keen interest to myself. The author explains his compulsion with entropy as related to the death of Smithson's older brother, who died before Smithson was born. Boetteger argues that being a "replacement child" led him to his "morbid preoccupation with the topic of death and with naturally occurring catastrophes". Critics also argue that Smithson’s connection to entropy can also be related to his brother’s death from cancer: the body's interior and exterior entropic disintegration.

In his earlier work, Smithson maintained a preference towards crystalline structures and process rather than that of organic shapes and materials. In 1966 Smithson’s story, “Crystal Land” was published in Harper's Bazaar and chronicled a “rock hunting adventure” with his wife and another couple. This acted as the first publicised proclamation of his shifting interest from “discrete crystals to that of desolate land”. This was an important move in Smithson’s career that went on to influence his later and most important works.

toward the development of an air terminal site_

Towards the end of Chapter 3, Boettger goes on to critique Smithson's essay entitled “Towards the Development of an Air Terminal Site” which was written during the fated collaboration between Smithson and the T.A.M.S. development group in the late 60’s. Boetteger refers to the essay as a ,“a very ambitious piece, suffering from its juxtaposition of abstract thinking and only prosaic data…[the only thing to be extracted] was impressively detailed substantiation”.

I decided to review the article for myself.

I was immediately puzzled by the disjuncture of subject matter and contextual references. Smithson wanted to create a new kind of building that brought together “anthropology and linguistics through an esthetic methodology”. (in which non site provides an obvious model) However, he does not clearly explain how he is going to combine these disciplines. Smithson also fills the essay with tables and numerical data that dissect the text and create a piece that is difficult to navigate and therefore challenging comprehend the entirety of his conclusive(or non conclusive) ideas.

22.10.10

inbetween pt 2_BOUNDARY

Within the text, Land and Environmental Art, the prefacing survey by Bryan Wallis discusses how social practices can determine and evolutionize the site and therefore the experience. In the section, “Radical Dislocation”, Wallis characterizes early earthworks as “based upon on geographical or economic decentering..that were mostly urban oriented and were concerned with patterns of everyday life as well as the social organizations of space.” Projects such as Stanley Brouwns’s “This Way Brouwn” in which Brouwn instructed strangers to draw maps to varied locations addressed these new conceptual spatial interpretations.

Frieze Magazine provides a thoughtful review of Brouwn’s 2005 retrospective a the Van Abbe Museum that best captures Brouwn’s relationship with spatial representation and recording:

“This remarkable retrospective of this peripatetic artist’s career afforded an opportunity not only to reconsider Brouwn’s often overlooked work, with its origins in 1960s Conceptualism, but also to reflect on the legacy of that tradition in an age that seems less concerned with that period’s major preoccupations. Among these could be cited: the dematerialization of the work; the impersonality of creative processes, or the disappearance of the author; and, like the experimental literary group Oulipo, an interest in contingent rules and the permutations of a simple pattern. All of these things also appear in contemporary work, but today the focus seems to be on the personal life and self-exhibition, a desire to be immersed in experience without mediation, and the flaunting of rules, systems and codes.

Brouwn’s habitual obsessions are with geography, distance and direction, scale, measure and dimension. He is a meticulous recorder, giving every indication of keeping his counter and measuring stick close at hand. Between 1960 and 1964 he produced the seminal series ‘This Way Brouwn’, asking passers-by to sketch for him on paper the way from A to B, then appropriating their drawing by adding his stamp ‘This Way Brouwn’. Whether the artist is dealing with his own meanderings, comparing different units of measurement –1 royal cubit: old egyptian measuring unit of length 2500 b.c. (1998) and division of 1m and 1 wari (kenya) according to the golden section (1994) – proposing short walks in the direction of world cities – walk 4m in the direction of havana distance: 7396584.7166m (2005), measured from the very spot where you standing in the museum – or detailing in exact terms what lies behind a square metre section of the museum wall – ‘a 28mm cushion of air separates brick from sand-lime brick’ (1x1m wall exhibition space van abbemuseum eindhoven, 1979-2005) – a cool passion for precision seems to reign."

Wallis likens Brouwn’s mapping as well as other project confronting traditional ideas of spatial analysis, to what Edward Soja’s “spatialization of cultural politics, a radical rethinking of the intersections between social relations, space and the body..Soja cites in particular, French Sociologist Michel de Certeau’s notion of spatial practices to describe the way a physical place is embodied through social actions, such as peoples movements through it. Certeau’s analysis allows one to recognize in the work of 1960s Conceptual Artist ‘the clandestine forms taken by the dispersed, tactical and makeshift creativity of the groups or individual s already caught in the nets of the discipline”. These ideas of the site understood through its social activation became important to understanding and recreating the vernacular landscape. Many of the artists where confronting or addressing “specific historical and social environmental contexts even as they transformed the space”.

Dennis Oppenhiem’s Annual Rings, an earthwork that involved the artist etching concentric rings into the ice on the U.S.-Canada border. Oppenheim’s photographic documentation of Annual Rings is currently part of the Measure of Time Exhibit at the UC Berkley Art Museum and below is the curator's description of the photos:

“Cutting back and forth across the boundary line, his massive artistic marks on the land (certainly mocking the Abstract Expressionist–era dominance of the artist’s gesture) not only breached political borders, but also traversed time zones."

The concept of “geopolitical boundaries” in land art is especially interesting to me because of my mild obsession with mapping. The idea of moving along and redefining physical and conceptual boundary lines coupled with the realization that natural processes would shortly reestablish their own permanence and boundaries was a central concept in earthworks and spatial representation in the landscape.

13.10.10

inbetween pt 1_SITE

Thinking about the definition of "site” architecturally I instinctively reach towards the space or land that the design intervention will consider or integrate. This explication of the site is severely challenged in the philosophy and the idea of a “non-site” in the early installations and works of the early land artists. In the article, “The Site as Project: Lessons from Land Art and Conceptual Art”, author Martin Hague explores the constructs of site within modern architecture and land art. He argues for a closer association between site and process and calls for a new thinking of the site in architecture.

The ideas of “non-sites” and displacement are central to the understanding of site and process in many fundamental land art works, such as Richard Longs walks and the correlating maps he displayed. Hague suggests this physical connection to the landscape could be useful for the architect in understanding the “site”. “Long’s trajectories through the landscape also suggest new ways in which we might reconsider our own initial visits to a new site: for the architect such trajectories or visits typically include careful measurements of the land, taking account of its critical features, and the like. What becomes possible are site investigations that might reveal the qualities of a site that would otherwise remain latent with the use of conventional surveying techniques”.

During my landscape architecture studio this summer, before any design charrete or project, we would conduct a very thorough site analysis taking into account everything from neighborhood character to soil conditions. Many factors I would have not taken into consideration for a successful survey or sight analysis were carefully researched and dissected. This lent a holistic understanding of the embedment of the site in its environment.

Matta-Clark explores the idea of a previously constructed environments as the site for his projects, in particular “Fake Estates”, which brought to question neglected spaces in the urban environment. Making use of a building or previously constructed fragments, as Matta-Clark did, becomes an act of displacement and exploration of time processes.

Fake Estates

To reconceive site and project, we have to look to the site as a process or as Hague states, “a repository that is forever in the process of change. The importance of designing with the past and present in mind through historical events and natural processes has become increasingly important in many urban design projects. Understanding time as part of the site and process and removing the physicality of the space allows for more comprehensive design work.

Two recent landscape architecture projects that are designed to evolve over time, in space and experience are Fresh Kills and the High Line. Both boldly recognizing the importance of “site cultivation”, and as Keith Frampton suggests, “uncover dormant narratives and strategies”.

Fresh Kills

High Line

To be cont.

26.9.10

“a thing is a hole in a thing it is not.” Carl Andre

Susan Boettger opens her survey of the late 19th c.

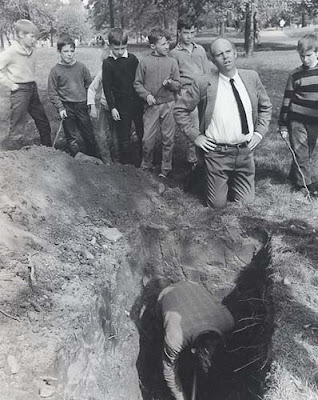

earthworks art movement, fittingly titled Earthworks, with Claes Oldenburg's piece the Hole. Oldenburg best known as a progressive leader in the pop art movement organized an excavation, adhering to the dimensions of a human grave, in Central Park on October 1, 1967. Entitled Placid Civic Monument, but referred to as the Hole or Burial Monument by Oldenburg in his notes, was part of an exhibition sponsored by the NYC Administration of Recreation and Cultural Affairs.

Oldenburg termed his recession in the ground of Central Park as an "invisible monument". The negative space created by the removal of topsoil is similar to Carl Andre's exploration of "holes" in his 1967 show at the Dwan Gallery. Boettger notes that while Oldenburg was not an earthworks artist, the element of "nonvisisbility,transience or geographical remoteness is another aspect aligned to practices fundamental to Earthworks".

3 weeks prior to the "excavation" similar ideas were explored in the exhibition 19:45-21:55 in Germany. 19:45-21:55 reference a twenty four hour time period was arranged by Paul Manez a curator and art director. 19/21 was an exhibition of "anti form" and included work from the artists Jan Dibbets,Richard Long, Barry Flanagan and John Johnson. The latter three sending boxes of organic materials with a list of instructions(some including additional collecting of materials), "in this way binding the gallery's interior to a reference of the natural environment".

The parallels between the the American and European earth works and post minimalism were unknown in the late sixties US. Boetteger connects the two using the Oldenburg's "Hole" because it corresponds to the early use of natural materials in art works in the US. and abroad.

The "Hole" was interpreted and referenced to as a "grave for dead art", "a wounded virgin" and "and a trench", among many others. But what existed to the public was open grave.

Chapter 1 Response

earthworks art movement, fittingly titled Earthworks, with Claes Oldenburg's piece the Hole. Oldenburg best known as a progressive leader in the pop art movement organized an excavation, adhering to the dimensions of a human grave, in Central Park on October 1, 1967. Entitled Placid Civic Monument, but referred to as the Hole or Burial Monument by Oldenburg in his notes, was part of an exhibition sponsored by the NYC Administration of Recreation and Cultural Affairs.

Oldenburg termed his recession in the ground of Central Park as an "invisible monument". The negative space created by the removal of topsoil is similar to Carl Andre's exploration of "holes" in his 1967 show at the Dwan Gallery. Boettger notes that while Oldenburg was not an earthworks artist, the element of "nonvisisbility,transience or geographical remoteness is another aspect aligned to practices fundamental to Earthworks".

3 weeks prior to the "excavation" similar ideas were explored in the exhibition 19:45-21:55 in Germany. 19:45-21:55 reference a twenty four hour time period was arranged by Paul Manez a curator and art director. 19/21 was an exhibition of "anti form" and included work from the artists Jan Dibbets,Richard Long, Barry Flanagan and John Johnson. The latter three sending boxes of organic materials with a list of instructions(some including additional collecting of materials), "in this way binding the gallery's interior to a reference of the natural environment".

The parallels between the the American and European earth works and post minimalism were unknown in the late sixties US. Boetteger connects the two using the Oldenburg's "Hole" because it corresponds to the early use of natural materials in art works in the US. and abroad.

These early earthworks were a response to a new understanding and awareness of the ecological environment as well the the socio-politcal unrest that characterized the Sixties. The idea of the work evolving due to natural forces or human interaction was key.

The "Hole" was interpreted and referenced to as a "grave for dead art", "a wounded virgin" and "and a trench", among many others. But what existed to the public was open grave.

As stated Oldenburg:

"By not burying a thing the dirt enters into the concept, and little enough separates the dirt inside the excavation from that outside..so that the whole park and its connections, in turn enter into it. Which meant that my event is merely the focus for me of what is sense, or in the corner of a larger field.."

Chapter 1 Response

21.9.10

ten minute birthday

celebrating the birth of the blog, welcome.

I am undertaking an independent study this fall on the subjects of land art(also earthworks) and environmental design the histories, intersections and relation to present day. Both,very broad subjects with many definitions and popular understandings. To fully understand this ambiguity and perhaps find for myself the defining terms or moments in each of these histories(or is it simply a single story?) I will start at the "beginning" with the great visionaries,artists,writers of the land art movement, before such a name existed, and explore there ideas and art works. For this research and exploration I will be primarily using the texts

_Earthwork: Art and Landscape of the Sixties by Susan Boetteger

_Land and Environmental Art by Jefferey Kastner and Brian Wallis

(as well as a few more I am patiently waiting for from ILL)

more to come, I will post back later this week the above readings.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)